The microbiological world is a vast domain of life occupied by organisms which are too small to be seen with the naked eye. Because of their diminutive size, its denizens are largely ignored, yet in terms of impact and numbers, they represent the predominate form of life on earth.

In the familiar settings of our towns and cities, the same microorganisms have established thriving and complex ecologies that are almost always overlooked, yet the very existence of these and the extent of their vigour, can act as a powerful barometer for the health of our own urban environments.

Microgeography, is an approach that explores the relationships between urban environments and their microbial and human inhabitants through walking and informed observation, and often via a variety of playful and inventive strategies. Its overriding aim is to take pedestrians off their predictable macroscopic paths and to jolt them into a new awareness of the vast, but nearly always disregarded, urban microbiological landscape. These microcosms of microbiological life reflect the health of our own cities and towns, and thus through the process of microgeography, the observer is invited to question the influence of human activity upon this urban microbiological landscape, and hopefully through this, to extrapolate the impact of our actions on to the more visible world beyond.

Below is a description of a typical microgeographical process that took place at the fabulous Bees In A Tin event on 12th June at Millennium Point in Birmingham. The 90 minute outdoor and mobile workshop comprised a short microgeographical walk, the observation of natural samples for microbes in situ using a poweful portable field microscope (200-1000x magnification) and an iPhone, and some alfresco preparation of DIY/Kitchen microbiological growth media, and related bacterial growth experiments.

The event began with a short microgeographical walk where participants were shown and guided towards a number of found and local urban microbial ecologies as detailed below.

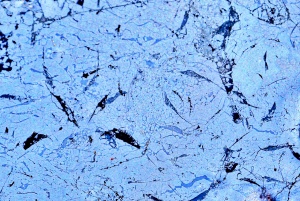

On a smooth and coated wall, ecologies of algae and iron oxidizing bacteria flourish in vertical streaks. The leaking fontain nozzles provide these with the water needed for microbial growth

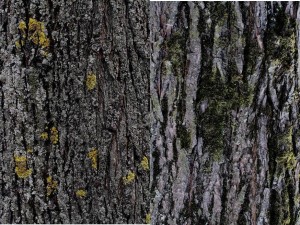

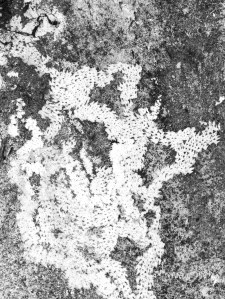

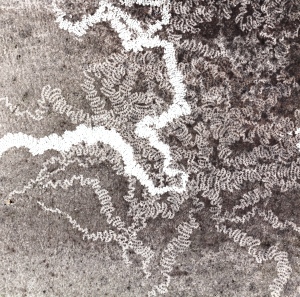

Over a period of many years a concrete wall has become covered in a dark patina of microbial growth. It might not look alive, but were we able to observe this thin layer with a microscope we would find an exotic and miniature forest inhabited by fungi, green algae and cyanobacteria. I call this ubiquitous but overlooked microbiological veneer, the Urban Cryptobiotic Crust (UCC). Here a snail, a leviathan on the scale of the UCC, has fed on this ecology, and in removing it and revealing the sterile manmade substratum beneath, has highlighted the wall’s microbiology and etched a telling metric into its extended surface.

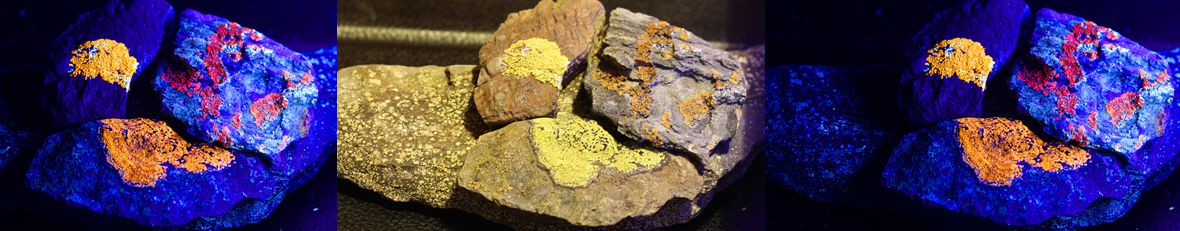

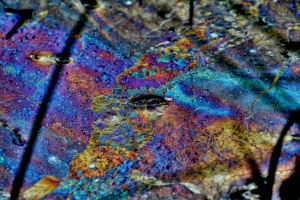

In the middle of Birmingham and beneath an urban roadside drain grating we find a rainbow-like community of iron, and perhaps even manganese, oxidising bacteria floating on the surface of the residual water. It’s brittle and breaks into tiny fractures when we throw in stones so we confirm that it’s not due oil or petrol. Then were uncertain, as we discuss where does the iron that supports this community come from in the middle of Birmingham. Ah, it’s in the wash off from the grate. Doh! And then there is a sense of wonderful closure, a sheen of heavy metal, forged in Birmingham like Judas Priest and Black Sabbath.

The portable and powerful Newton Field Microcsope was also used to observe samples for signatures and examples of microbial life but infortunately this activity was curtailed by the rain. Below though are examples of its portability and use in similar environments.

The Newton Field Microscope. Portable, poweful (200-1000x magnification) and compatible with an iPhone

An unassuming old cat food bowl harbours a wondrous and thriving microbial ecology including Rotifers and Waterbears.

After some alfresco preparation of DIY/Kitchen microbiological growth media, participants then inoculated the various growth media with found objects of their choice. The images below are of the microbes (mostly bacteria and a few moulds) that grew on the agar plates. The way that this usually invisible life emerges from the chosen objects, and the complex manner in which seems to embellish these, to me, forms a very potent reminder, of not only the ubiquity of microbiological life, but also its intimate connection with all else.

Next, and back in my microbiology laboratory I selected some of the naturally pigmented bacteria that we had isolated.

A pallette of living colours. Naturally pigmented bacteria isolated from a microgeographical walk in Birmingham.

Finally, I carefully dried down the coloured bacterial colonies so that they and the agar formed a glassy state. Not only are the bacteria and their own stories now beautifully preserved, but the thin and brightly coloured films might also in future become part of unique jewellery, bacterial sequins for ball gowns, and even bacterial stained glass for novel lampshades.

The glassy bacterial films can also act as unique lenses through which the normally invisible microbial world can be directly projected into the one that we normally see as can be seen below

The film has been used to project the dried bacterial colonies onto a wall using an overhead projector